Approaching Performance Art: Marilyn Arsem’s Bodies in the Land

Encountering performance art can be surprising. You walk into a room and notice a person engaged intently with some task. You might wonder what they are doing and if you should even be there. Don’t panic! Take some time. Instagram scrolling leads us to think we understand what we see in mere seconds. Art asks us to slow down and consider what we see in a more deliberate way.

Approaching performance art is similar to attending a wedding or graduation. These ceremonies are familiar types of performances with symbolic objects and actions. Performance art may seem more puzzling since the artist is likely engaging with objects more symbolically ambiguous than a wedding ring, and as the artist interacts with those symbols, ideas emerge. Objects in performance often function symbolically, as they might in a painting; however, performance artists, such as Marilyn Arsem, create experiences rather than static images. This requires time to understand.

In her 2022 work, Bodies in the Land, Arsem performed for 59 hours over six consecutive days at the Momentary. The content of such durational pieces becomes clearer over time. This doesn’t mean viewers must see the entire piece to get something out of it. I was able to watch segments of the performance on each of the final three days, but I would have gleaned some meaning even if I had been there a shorter time. Here’s what I observed:

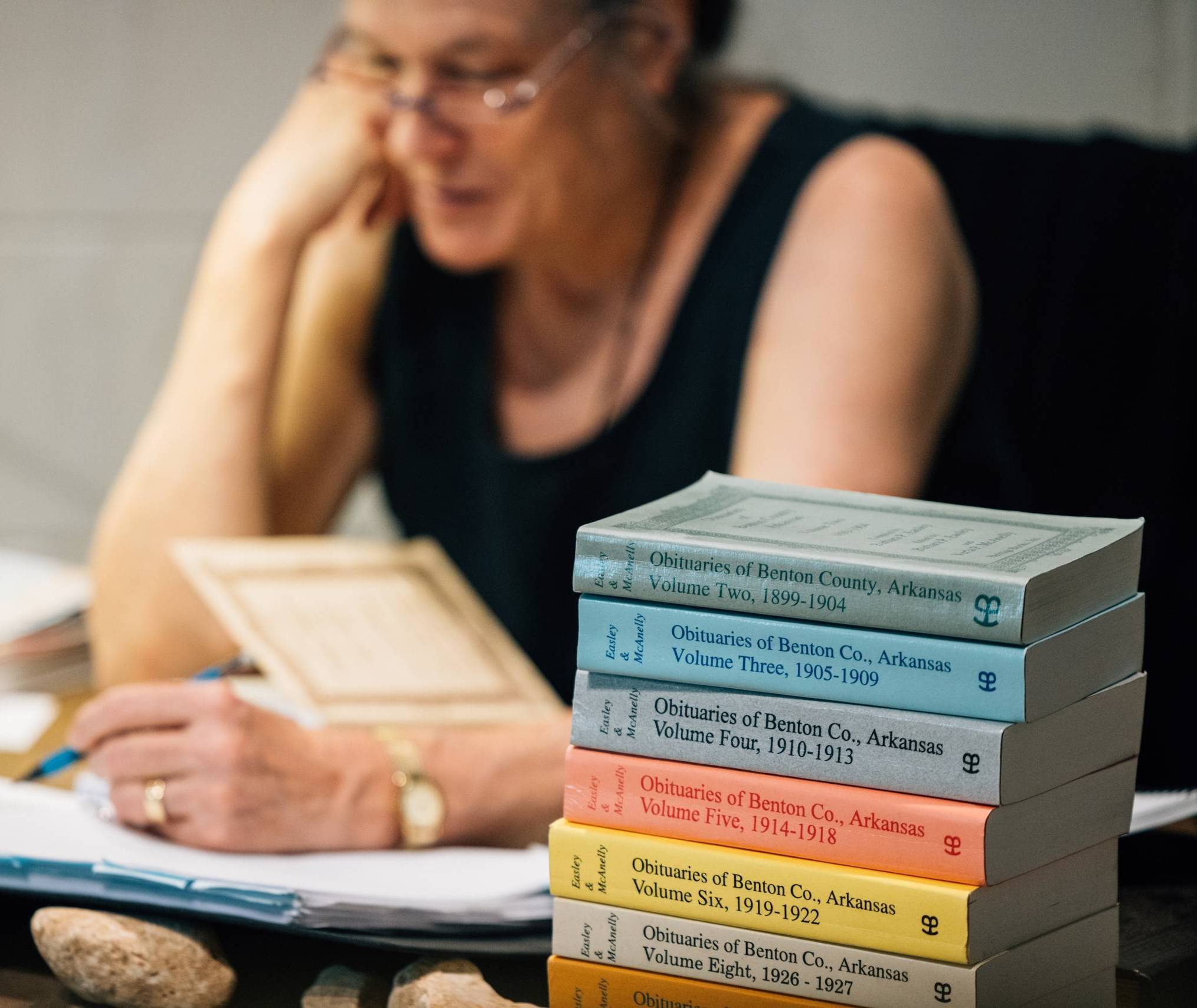

Arsem performed in a narrow room with a table stacked with books. Pale orange stones covered the entire floor. For long periods, she read late nineteenth-century newspaper obituaries. The tone of these notices was surprisingly blunt. Accidental deaths were described in gruesome detail. Others told bizarre tales, such as the former choir boy who suffered a head injury and turned to a life of crime. Many women died after their dresses caught fire, and tuberculosis (or “consumption”) was alarmingly common. No hospitals were mentioned.

In total, Arsem read 676 obituaries. The majority were for men. A smaller number were for women and children and only about a dozen mentioned African Americans. Likewise missing were the accounts of Native Americans who, at this time, were being pushed farther and farther west. To supplement, she read from an account of the Trail of Tears. Recognizing these absences comes with the enduring presence required both to read and to listen.

Occasionally, Arsem walked around, carefully balancing on the stones. After collecting several smaller stones, she would arrange them in an outdoor courtyard. Initially, she placed them in a grid pattern, suggesting tiny headstones, and later she placed them in flowing organic lines. The actions of reading and arranging the stones seemed connected. The stones, like the subjects of the readings, were from Benton County. This relationship was further emphasized when Arsem laid down on the rocks. As she arose, ghostly orange dust clung to her black dress. Who existed? What documents their existence? What traces remain?

Arsem’s performance seems to propose that a place cannot be fully understood by capturing a beautiful view in a picture. Rather, the landscape is a site of lived experiences, and history records certain lives while others are erased. Experiencing this complex work may lead us to consider how our own lives relate to, or impact, the land we live on, and how we might be remembered (if at all) in the future. Do the lives of distant strangers have resonance with our lives today? If their strengths and weaknesses reveal something about our shared culture, I’d say yes. As with any art, you may take home other ideas I missed. The important part is to give the art time to speak to you.

Written by Jeff Rufus Byrd

Byrd is a performance artist and writer with essays published by Performance Research and Live Art Almanac. You can see his work at JefferyByrd.com.

Photography by Jared Sorrells.