Bearing Witness: Imaging the Ineffable in Richard Mosse’s Broken Spectre

BY JONATHAN GRIFFIN

A camera can be many things to many different people. But nearly everyone on Earth has strong opinions about what it means to be photographed or filmed – even the indigenous tribes that Richard Mosse encountered deep in the Amazon rainforest during the making of his film Broken Spectre.

The Yanonami people live largely without electricity or technology, and have been the subject of anthropological and journalistic interest for decades. They have also experienced the incursion into their pristine territory by illegal wildcat gold miners, and have suffered the dire consequences of environmental contamination, disease and violent displacement as a result.

When Mosse traveled in 2021 to the remote Yanonami village of Palimiu, near the border between Brazil and Venezuela, he naturally took his camera. He wanted to document the ongoing conflict which he saw as an essential story in the broader narrative of environmental catastrophe currently unfolding across the region.

When the villagers assembled to address Mosse and his collaborators – cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and sound designer Ben Frost – one young woman, Adneia, stood forward and delivered a blistering tirade against Brazil’s then-president Jair Bolsonaro. But subtly, her focus shifted to the filmmakers themselves. “If you’re just here to film us for nothing, that’s bad!” she said. “You white people, see our reality, open your minds.”

Adneia understood what it can mean to be filmed or photographed. Mosse understands it too, and was impressed by Adneia’s clear-eyed acknowledgment of the power imbalance between the camera and its subject. Her speech forms the crux of Broken Spectre.

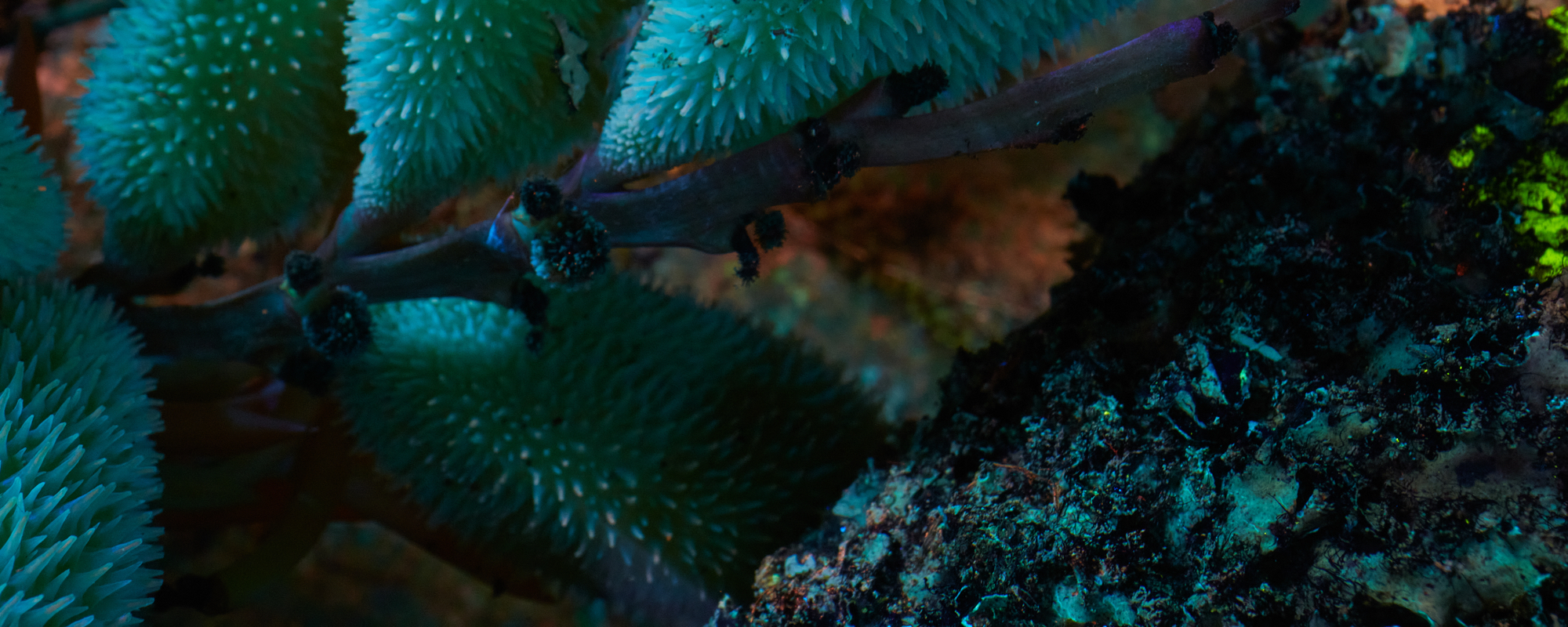

Mosse has often been drawn in his work to what he calls “aggravated media.” Infrared film, which he used to document the military conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, was invented during the Second World War to expose camouflaged vehicles and encampments. In his film Enclave (2013), the lush greens of Congo’s landscape and of paramilitaries’ uniforms are transformed into a palette of lurid, disorienting pinks.

The thermal imaging camera Mosse used for a subsequent project about the European refugee crisis is officially classified as a weapon. Sometimes shooting (to use that loaded term) from miles away, Mosse used the camera to track the movements of people in refugee camps, or sheltering in battlefields. While his intention was to shed sympathetic light on the plight of his subjects, Mosse also drew attention to the privileged distance from which he and his audience witnessed it.

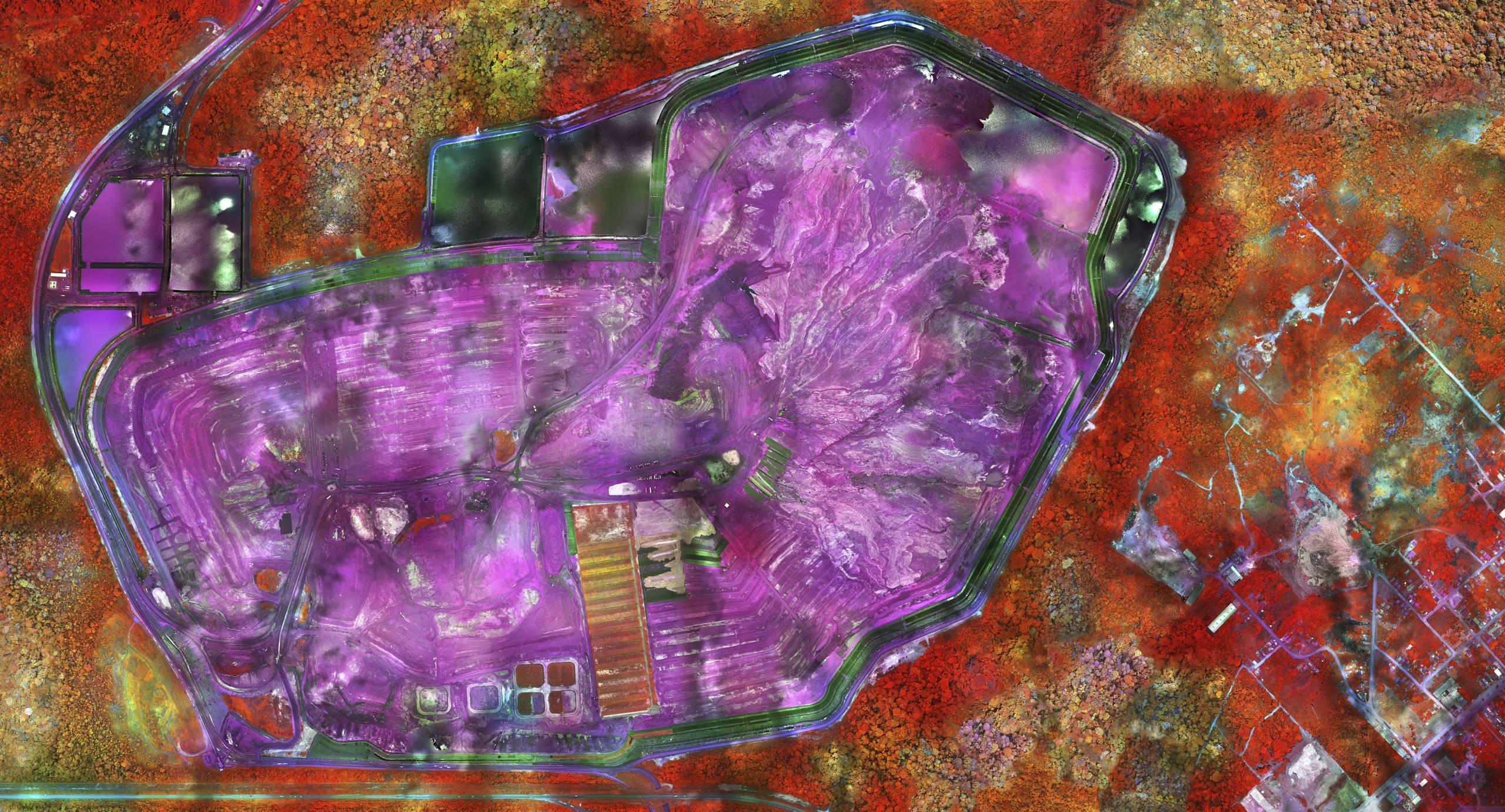

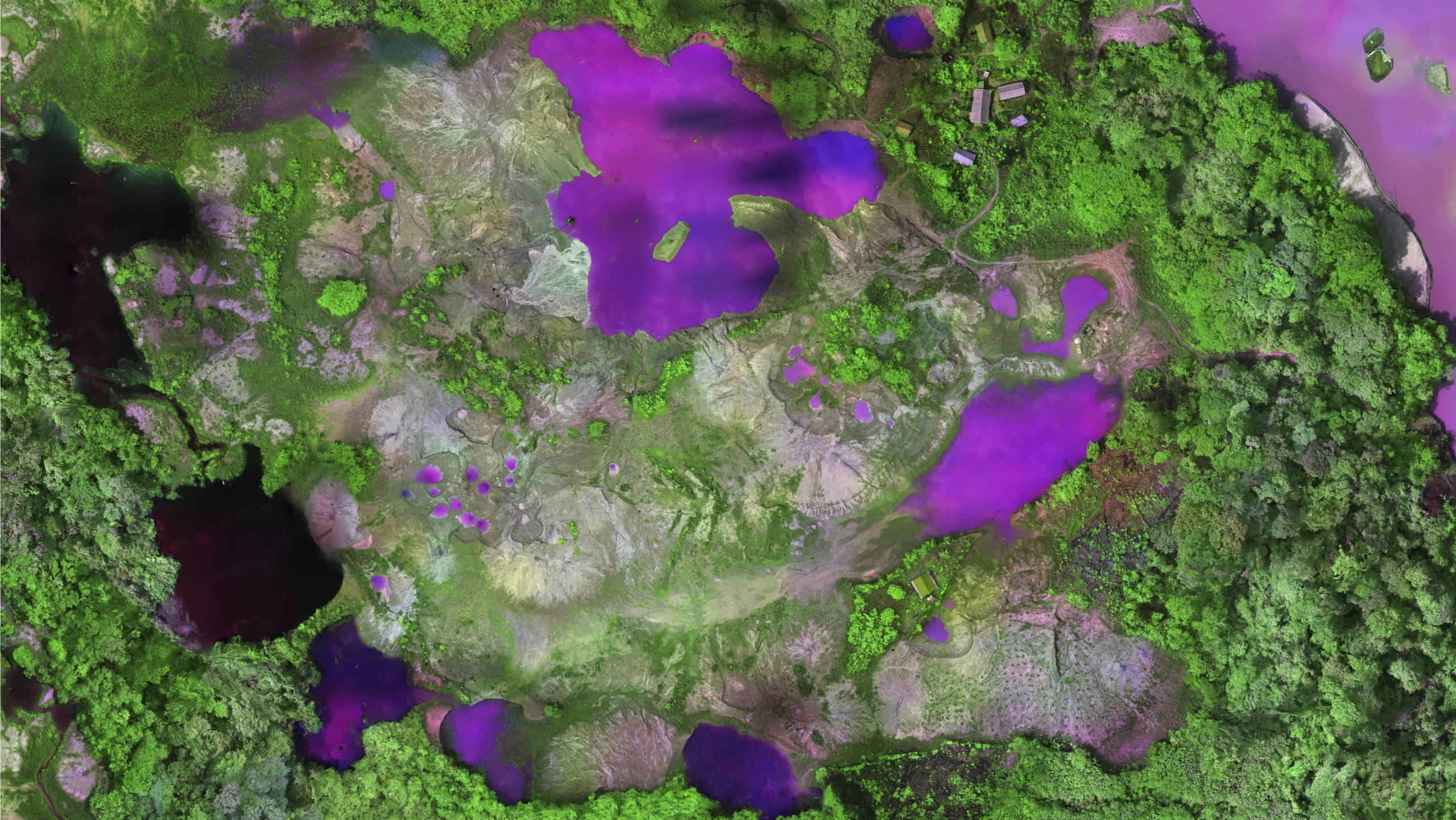

In the Amazon, Mosse used a multispectral drone camera to make composite maps of the landscape. Sensors in the camera detect wavelengths beyond what is ordinarily sensible by the human eye, thus transforming the endless greens of the forest into a palette of artificially-assigned hues. The technique has long been employed by scientists to chart the degradation of the rainforest. However, similar drone cameras are used by farmers to establish which parts of their land are most fertile (or least depleted). Drone operators advertise their services on billboards by the side of the Trans-Amazonian Highway – a busy commercial route through the forest.

“The camera is looking at the forest as an asset,” Mosse says. “This is the corporate gaze of resource extraction.”

A drone is also associated with surveillance. Since it is estimated that 99% of the deforestation in the Amazon is illegal, many of the people whose land Mosse was attempting to photograph were understandably suspicious of what he called “three gringos up to no good.” Mosse described hiding in bushes to fly his drone over areas of illegal mining and deforestation, then running away when the drone descended for a battery recharge, revealing his position.

The Amazon can be a dangerous place for environmentalists, as proved by the murders in 2022 of journalist Dom Phillips and activist Bruno Pereira. The makeshift towns that have sprung up to service the needs and desires of wildcat miners (known in Portuguese as garimpeiros) are lawless and unpoliced. In order to get the images and footage he needed for Broken Spectre, Mosse often had to win the trust of people doing questionable – if not outright illegal – things.

Instead of a digital SLR camera strapped to his chest, as preferred by most photojournalists, Mosse carried a cumbersome large-format wooden box camera. In rural parts of South America, before the advent of the smartphone, itinerant photographers would operate a similar camera to make commemorative portraits at special occasions. They are still known as “lambe lambe” cameras – a name which translates as “licky licky”, probably referring to the need to lick the back of the film. Many people Mosse encountered had fond memories of the “lambe lambe” photographer, and his camera became a talking point. Tweeten’s 35-millimeter film camera was also unlike the cameras used by television crews; Mosse says that people instantly understood that what they were shooting was not going to appear on the nightly news. He sometimes told people they were making a Western movie. “Ah, you’re crazy artists!” people would conclude.

Except that Mosse, Tweeten and Frost are not crazy. The film they made, as well as the body of photographic work Mosse produced alongside Broken Spectre, is an astonishing, devastating feat, pressing at the very limits of representation. It is not so much concerned with indicting the people who appear in it as much as implicating all of its viewers in the mechanisms that enable the destruction of the Amazon to take place.

Written by Jonathan Griffin

Jonathan Griffin is a freelance writer and art critic. Born in London, he now lives in Los Angeles. He is a contributing editor for Frieze magazine, and has written for publications including The Financial Times, The New York Times, Art Review, Art Agenda, CARLA, Apollo, The Art Newspaper, Flash Art, Aperture, Art in America, Domus, Mousse, The Guardian, The Telegraph, Cultured, LALA, Modern Painters, The Brooklyn Rail, Tate Etc., Royal Academy Magazine, Wallpaper, Kaleidoscope, Texte Zur Kunst, Los Angeles Review of Books, Paper Monument, East of Borneo, Sotheby’s magazine, Tank, Manifesta Journal and The World of Interiors.