Momentary Flag Project: A Q&A with Artist Gabriella Sanchez

On October 7, the Momentary Flag Project welcomed its second flag designed by Los Angeles-based artist Gabriella Sanchez. Sanchez is a multidisciplinary artist best known for making vibrant paintings that challenge viewers to reconsider how we assign meaning to text and images in today’s visual culture. Drawing on her former career as a graphic designer, Sanchez’s compositions appear at once familiar and coded with a myriad of messages.

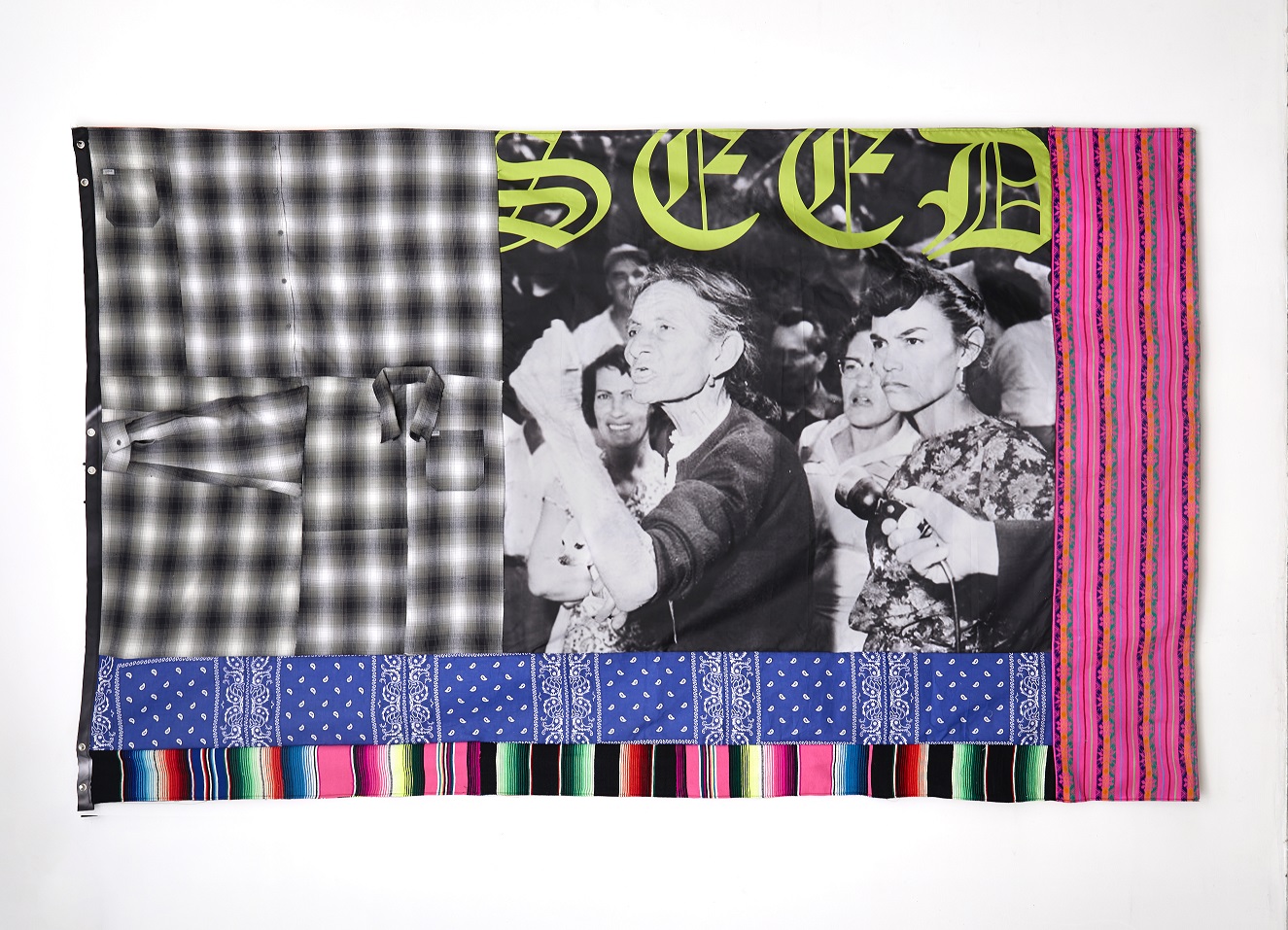

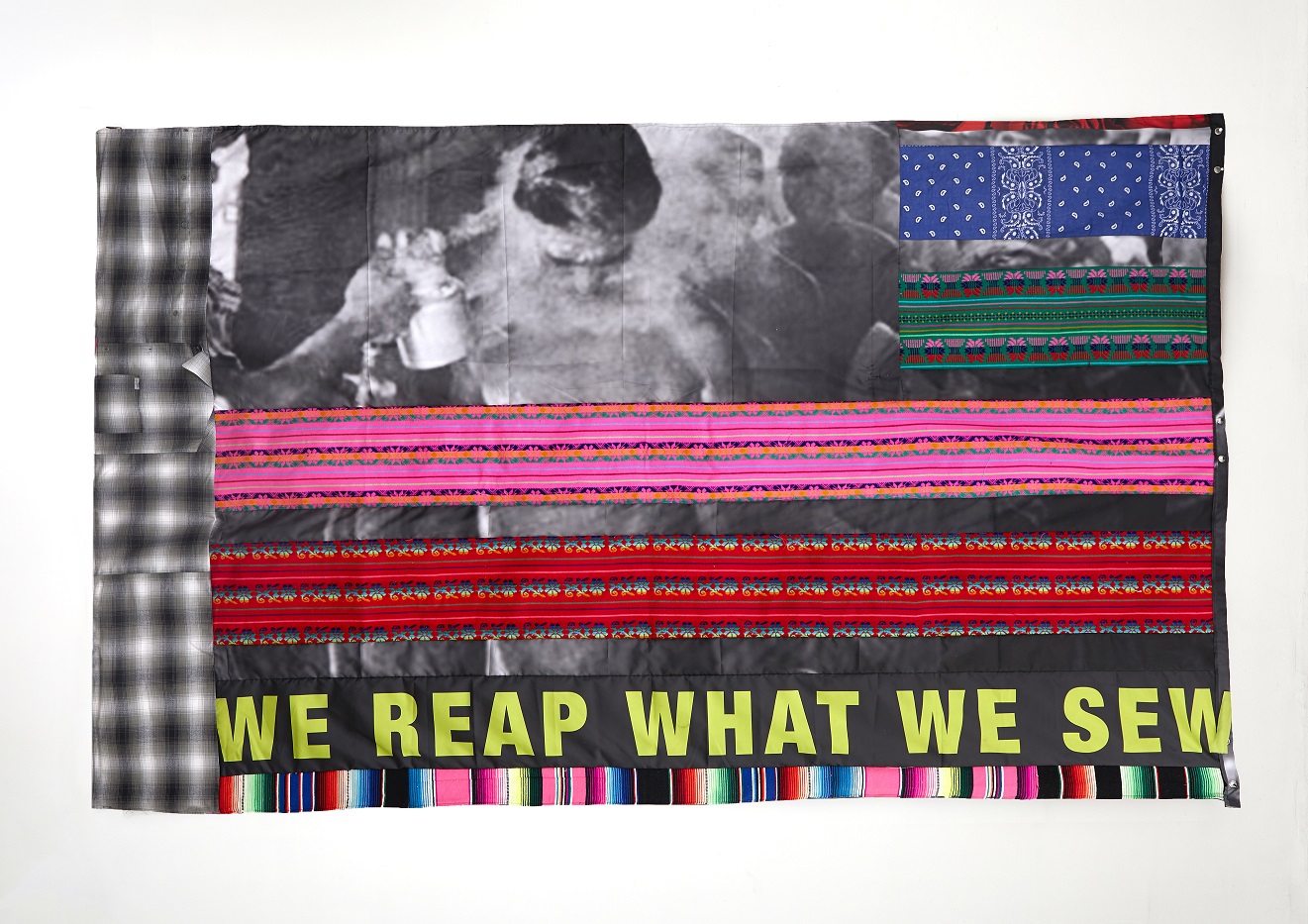

For the Momentary Flag Project, Sanchez designed a dual-sided flag that explores her relationship to land and country, which ultimately grapples with what it means to be both Mexican and American. Read the Q&A between Sanchez and Assistant Curator Kaitlin Garcia-Maestas as they discuss the meanings behind the flag and its materials.

Kaitlin Garcia-Maestas: In most of your work, you’re building your imagery off a blank canvas. Was it challenging to create a design for a flag, an object ascribed with so much weight and authority?

Gabriella Sanchez: To make this piece, I had to contend with the thing itself, that is to say, I had to contend with the idea of a flag itself. Instead of creating a painting that could be used as a surface design for a flag—essentially relegating my painting to the decorative—I wanted to create the thing itself. I wanted to create a flag. To do that, I had to reflect on my own relationship to the flag and in doing so, to this country. It was uncomfortable, but it was also rewarding.

KGM: I must admit, you really dove headfirst into this project. Not only did you design a flag, but you also made an absolutely stunning tapestry. Why did you decide to include found fabric in your flag?

GS: One of the first questions I had to answer for myself was what material this flag should be made of. I thought about using clothing from my own closet and that of my family, but I didn’t want to give that up. I didn’t want to give up our memories with my mom’s dress, my dad’s flannel, or my own shirt to be collected and kept by someone else. I thought about how I use photographs of my family in my paintings, but how I never use the original photos themselves. Those I keep for us. So instead, I decided to use fabrics that had never been used before, but still held reference to me and my family, which then made these fabrics and patterns symbolic.

KGM: Can you tell me more about how these textiles are symbolic to you and your family?

GS: I used textiles that would relate to my identity as Mexican American, the sentiment of being from ‘here’ and ‘there’. I used bandanas and plaid shirts that looked like the plaid shirts my dad, uncles, and cousins wore and still wear, like the one that I still have hanging in my closet now and the various bandanas I still have in my sock drawer that are well worn and soft. I also used “Mexican” fabrics that stem from Indigenous cultures within Mexico, but also beyond its borders, as you see similar motifs and color patterns from these textiles in many Indigenous cultures across Latin America.

KGM: In addition to adding super vibrant pops of color to the flag, the fabric also frames the black-and-white photographs. Who are the people in the photos?

GS: On one side, I used an image from the Chavez Ravine evictions in Los Angeles in 1959 which were carried out to make way for Dodger Stadium. In this photo, you see members of the Arechiga family arguing with officials about the evictions as a hand from the press reaches in with a microphone to record the exchange. The women are in obvious defiance of their eviction. The Arechiga family even continued to stay on the land in tents and trailers after their home was demolished until 1961.

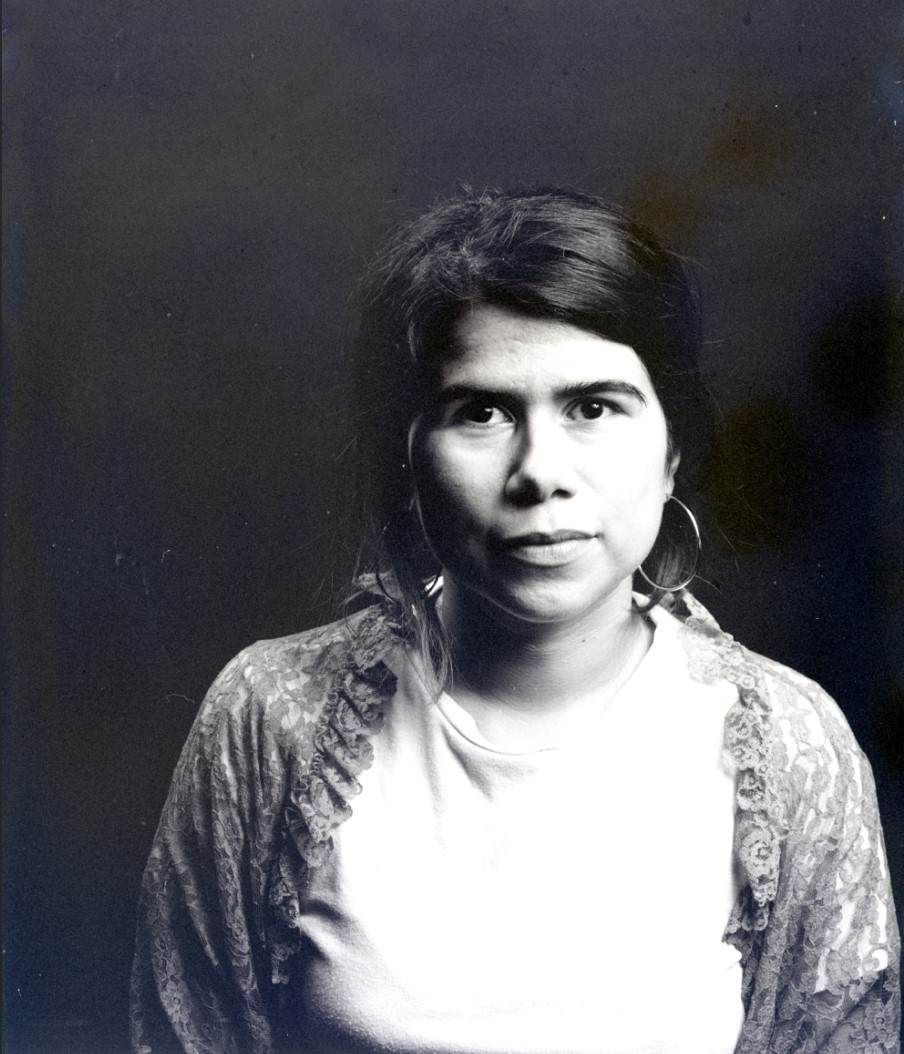

On the other side, I used a photo that references the Bath Riots in 1917, when laborers coming across the Mexico-US border were required to strip and be fumigated with toxic chemicals such as gasoline, pesticides, and Zyklon B. The Bath Riots began when Carmelita Torres, who crossed the border every day from Juarez to El Paso to clean houses, one day refused to comply with this practice and convinced others to resist alongside her. This uprising was quelled by US and Mexican troops and Carmelita was arrested. The practice of these “baths” continued at the border for decades afterward. Later in WWII, the Nazis adopted this practice of using Zyklon B as “disinfectant” at their borders and concentration camps. This later led to the construction of gas chambers which Zyklon B was also used for, killing millions.

KGM: Text is such an important element in your paintings, and you also chose to incorporate text into your flag. How did you arrive at the phrase WE REAP WHAT WE SEW and the word SEED?

GS: In the photo referencing the Bath Riots, you see a hand reaching into the frame to “fumigate” laborers coming over from Mexico to work in the US. The words “we reap what we sew” are written along the bottom. This phrase is left up to the viewer to determine who the “we” is that they themselves are a part of: the hand reaching in to fumigate, or those enduring this practice for survival’s sake. The word “sow” is changed to “sew” to allude to the actual construction of the flag and also to a joining, fastening, repair—a process of making anew.

On the other side, the word “seed” enacts the idea of a beginning, of new growth, both literal and metaphorical, as both plants and ideas can be planted and grown. The word “seed” and the phrase “we reap what we sew” also relate to the land (territory) that a flag represents.

KGM: While it’s still uniquely your design, your flag contends with some of the same themes as the United States flag, such as: land, opportunity, and honoring those who have fallen at the hands of a colonial oppressor. Can you speak to these references?

GS: On one side of the flag, you’ll see a loose mimicry of the stripes on the US flag, which are said to reference the 13 colonies, with the red symbolizing hardiness and valor and the white symbolizing purity and innocence. In the same way the stripes on the US flag are said to symbolize those lost in war, this flag, too, remembers those we’ve lost and continue to lose to white supremacy—those who have been marginalized and criminalized, many of those who wore and knew these textiles. But this remembering is not wholly sorrowful and can lend itself to celebration or galvanization, as a flag seeks to do…as long as there are those of us who still wear, use, and know these patterns and symbols—which is to say as long as there are those of us who remember where we came from and will continue to do so.

Stop by the Momentary and see this flag on the building’s historic flag pole on E St.