The Stoop and the Door: Recounting James Harrison Monaco’s Paulownia

Tell me a story.

That was my number-one request to my mother as a toddler. Struggling through her first cup of coffee, my mom read story after story each morning from the carefully curated stack I presented her, pulled from my bookshelf the night before.

Back in August, I attended James Harrison Monaco’s performance of Paulownia with that same anticipation: tell me a story. I had only the vaguest of ideas of what the story would be about, yet after watching YouTube videos of Monaco’s past performances, I was eager to be swept up in the poetic prose of a part-lecture, part-drama, accompanied by ethereal sounds.

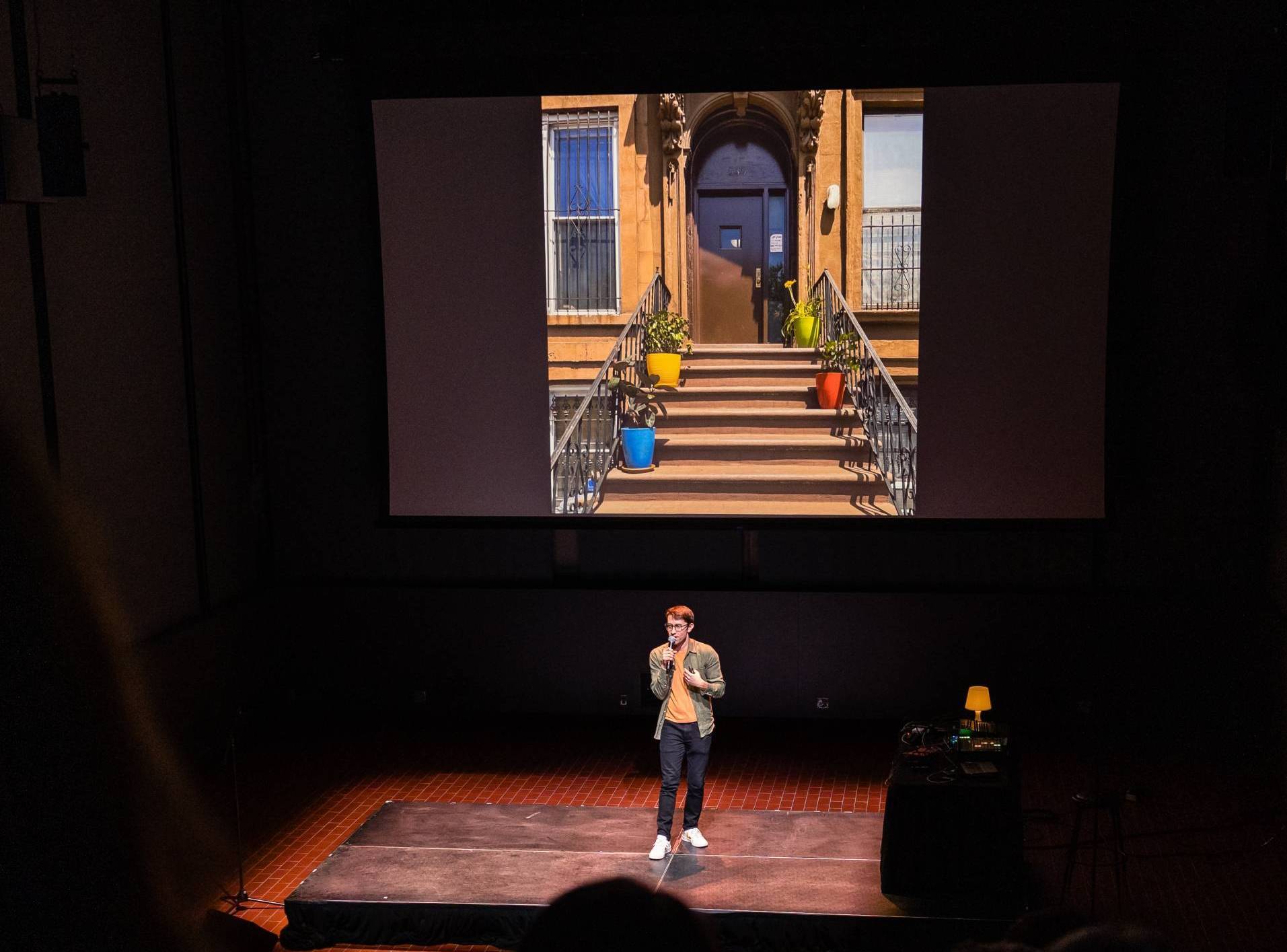

We were first taken on a plant tour of Monaco’s neighborhood in Bedstuy, Brooklyn. In a reflective exercise, Monaco noted that the four plants he and his girlfriend picked out to adorn their stoop all originated in eastern and southern Asia. Furthermore, the trees that grow in unsuspecting urban areas around his walkup brownstone were identified as paulownia trees, also known as foxglove or empress trees. Paulownia trees are native to southeast Asia (this factoid will be important later) and are the fastest-growing hardwood tree in the world. They can grow in areas that lack good quality soil and are seen sprouting in urban environments between pavement cracks and in other obscure places.

These observances formed the entrance to the rabbit hole Monaco fell down, taking all of us with him in his captivating storytelling performance.

Paulownia was constructed during Monaco’s residency at the Momentary and made specifically for the space in collaboration with Media Designer Shawn Duan and Director Annie Tippe. It was presented during the run of the Momentary-organized temporary exhibition A Divided Landscape, which brought together the works of seven contemporary artists confronting the historical and cultural narratives of the American West. The contemporary works were on view in tandem with historical drawings and paintings from the Crystal Bridges collection by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, George Catlin, Jasper Francis Cropsey, and others that speak to the preservation of the dominant frontier narrative.

What is an obsession without a curiosity?

What is a landscape painting without care?

What am I being influenced by that I refuse to recognize?

In the simplest of terms, Monaco’s overarching thesis explored the potential relationships and influences that eighteenth/nineteenth-century European and American landscape paintings (think Thomas Cole, etc.) took from sixteenth-century Chinese and Japanese landscape paintings. While he noted that there were no discernable, research-based links between Eastern and Western influences that he could find, Monaco explored his hypothesis through the art available to him at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

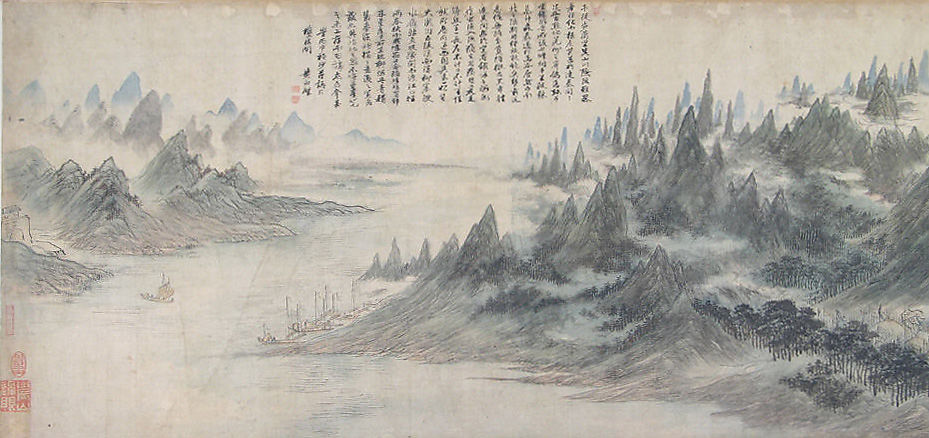

Monaco wondered, what happens when we look at “Western” landscape paintings with the standards of a Chinese landscape scroll? In examining several landscape paintings from the Asian art collection at the Met, he talked about how one does not “look” at a Chinese or Japanese painting; rather, the viewer “reads” the painting by examining the coda fonts. For example, the 1656 painting titled Searching for My Parents by Chinese artist Huang Xiangjian tells the story of the artist’s perilous journey through the Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces to reunite with his parents.

According to the Met, “in 1643 Huang’s father was appointed county magistrate in Yunnan, and for nearly a decade thereafter, Huang heard nothing from his parents. Not knowing whether they had survived the ravages of warfare following the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644, he set out in 1652 from his home in Suzhou and traveled over 1,400 miles in search of his parents. In his vivid published account, Huang describes the many hardships he endured before being reunited with his parents in rural Yunnan. He eventually escorted them back home, completing his round-trip journey in 558 days.”

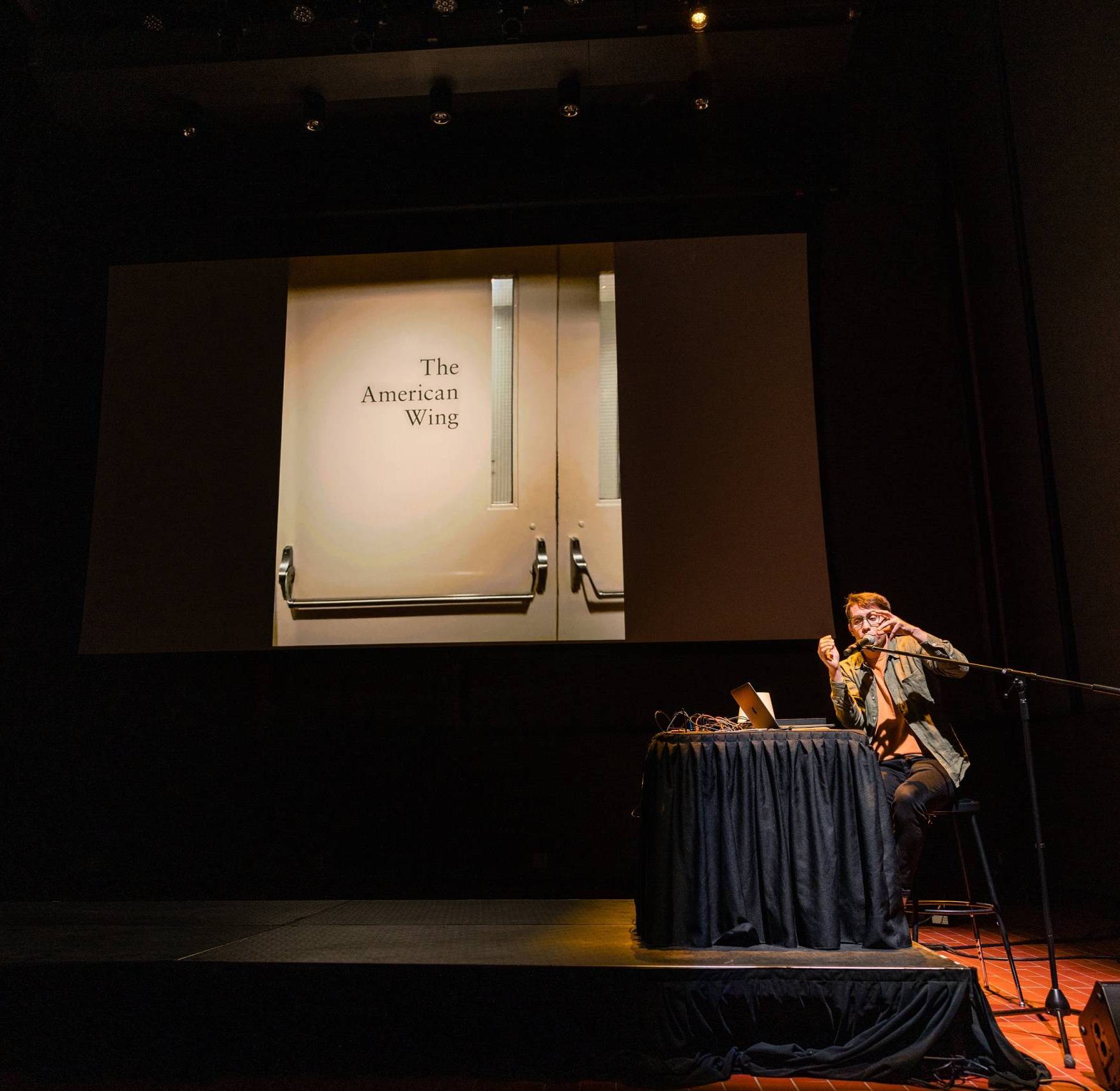

At the back of the Asian art wing of the Met, Monaco explained, there’s a door, obscurely hidden, that leads to the American art wing. The galleries were designed by Wen Fong, Chairman of the Department of Asian Art and the Museum’s Douglas Dillon Curator of Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, who spent 30 years developing and progressing the Met’s Asian art collection. Monaco pondered what the door might mean in connecting Asian art to American art, and so he stepped through.

Another standard of Chinese and Japanese landscape paintings is inserting the artist as a figure into the scene. Huang inserts himself into Searching for My Parents several times, in fact. Monaco explained this as we moved on to exploring European and American landscape paintings, and we found “Waldo” in one of Thomas Cole’s paintings: View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (1836).

According to the Met, “Cole’s unequivocal construction and composition of the scene, charged with moral significance, is reinforced by his depiction of himself in the middle distance, perched on a promontory painting the Oxbow. He is an American producing American art, in communion with American scenery.” Almost two centuries earlier, Huang was a Chinese artist producing Chinese art, in communion with Chinese scenery.

So, perhaps there are some influences after all?

The latter half of the performance showcased a flood of these types of influences Monaco found. Even dating back to Renaissance times, there are paintings of figures holding Chinese porcelain vases depicting landscapes. I smiled when Monaco played a recorded Zoom video of himself showing these findings to his performance partner Jerome Ellis, who listened with interest and attention but was almost certainly the first “audience member” of this lecture. I loved seeing Monaco’s enthusiasm in his findings, as if he’s spent his entire life searching for these answers and is imploring his friends to be just as excited about an obscure topic as he is. But he laid bare his findings with poignant questions for the audience: What is an obsession without a curiosity? What is a landscape painting without care? What am I being influenced by that I refuse to recognize? After the show, I asked Monaco how he determines which stories will make the best performances. “It’s usually something I can’t stop thinking about,” he replied. Clearly, this was a story he could not stop thinking about.

Furthermore, Monaco was overcome with giddiness sharing the story of a sixteenth-century Chinese painting by an unidentified artist. The painting is titled Playing the zither for a crane and features a man playing music for his crane beneath a massive paulownia tree. Monaco exclaimed, “This is what I do every day! Making music on my synth with a paulownia tree in the backyard.” It was impossible not to share the same enthusiasm Monaco exerted–and for a topic I knew nothing about merely 30 minutes earlier. And therein lay the magic of the performance–the ability to be swept away on the words of a gifted storyteller playing ambient music, coming back to reality an hour later having learned something new.

At the end of the journey, we returned back to the stoop with one last story of the paulownia. Monaco explained that before the invention of styrofoam, the packing material that was used to transport Chinese porcelain to the United States and elsewhere…was paulownia seeds. Opening the carts at their destinations, the seeds would get picked up by the air and sent into the world to seed and populate. The sentiment was not lost on me. While we may not be able to prove the direct links of influence we share across cultures through data or written word, the proof is there all the same.

At the top of the performance, the audience was told that Paulownia was a work-in-progress. After the performance, I asked Monaco and Duan how they knew when a work was finished. Monaco responded with an unattributed quote: “No painting is ever finished, it’s just abandoned.” Duan simply said, “I don’t finish projects; I just let them go.”

Written by Erica Harmon, editor, the Momentary and Crystal Bridges.